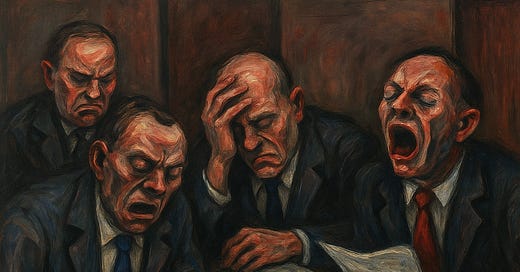

Even by the low and falling standards of British governance, one might expect a Strategic Defence Review to contain a great many concrete recommendations for Defence. Failing this, it surely should lay out a credible grand national strategy, even if the detail is lacking. Somehow Lord Robertson (former Secretary of State for Defense 1997-1999 and NATO Secretary-General thereafter), General Barrons (Joint Forces Command 2013-2016) and career academic Fiona Hill have failed to do either, after a year of work. To say so much nothing for 47,000 pages is quite a remarkable achievement.

Perhaps little more should have been expected. All the reviewers have spent their careers deeply embedded in the institutions of the crumbling “liberal international order”. A break from the reflexive, unthinking Atlanticism of the postwar years was never really on the cards. Hill, who has US citizenship, was on the National Security Committee during the first Trump administration, and is a Russia hawk and friend of John Bolton (would any other country let a person so deeply embedded in another country’s national-security apparatus exercise such influence over their own policy?). Robertson became a Labour MP in 1978 and oversaw the publication of the 1998 Strategic Defence Review, well-received at the time but subsequently made to look rather irrelevant by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the kinds of protracted conflicts that were at the time thought to be a thing of the past. Barrons has spent his entire career in the Army, not exactly an institution known for promoting independence of thought.

Rumour has it that the publication of the Review was delayed for many months due to a bruising fight with the Treasury over the affordability of its recommendations. Much time and trouble could perhaps have been saved by simply choosing an economist with some knowledge of the country’s fiscal position as one of the Reviewers. Even more time would have been saved by also finding a specialist in political economy (our services are always available at very reasonable rates). This would hardly have been difficult and the logic is obvious. You can only have the defence budget that you can actually afford, given the existence of real-world political constraints. These too are obvious. As Philippe Lemoine has explained at great length, voters simply do not care that much about Ukraine or other elite foreign policy goals relative to domestic policy objectives they hold dear (like low inflation, a working healthcare system, police that turn up when your bike is stolen).

Unfortunately, when the country has seen over 15 years of economic stagnation, public services are in decline, and living standards are likely to fall over the course of the Parliament, these political constraints are particularly acute. The war in Ukraine may well rumble for another few years but will end one day. Trump will not be President forever. Expecting public consent for a large and sustained increase in the defence budget is simply absurd, absent radical economic reform to improve the country’s growth prospects. If the Review’s Atlanticist authors wanted their few concrete recommendations for the MOD – which span many decades of procurement – to become reality, what they actually needed to do was spell out a credible economic growth strategy. This, unfortunately, would likely have exposed the problem that elite foreign and domestic policy preferences are to some considerable degree growth-constraining. A forever proxy war with the local gas station is hardly beneficial for Europe’s growth prospects, just to put it very mildly. The costs of lost Russian gas could of course be mitigated to some degree by fracking Lincolnshire, but this again goes against other elite preferences.

The absence of serious strategy from the Review emerges in other ways. Recruitment is a severe and growing challenge for all branches of the Armed Forces, especially the Navy (which the Review acknowledges). In part this is due to problems with pay and conditions, but in part also due to declining propensity to serve. Recent surveys of Gen Z indicate that just 11% would willingly fight for their country and 41% would not serve under any conditions whatsoever. To this the Review lamely proposes a “national conversation led by the Government on defence and security” and expanding the Cadet Forces.”

This above all illustrates the disconnect between the worldview of the Reviewers and the world they actually live in, where massive forces of demography, technology, and economics are rapidly severing traditional links of mutual loyalty between the state and its people. The Review has nothing whatsoever to say about the fissures brought about by mass immigration and recently brought to prominence by riots. Coupled with the ever-present issues of Scottish independence and small boats, the UK has very obvious and severe long-term domestic security issues that no amount of freedom of navigation operations in the Taiwan Strait will make disappear, for all that they make Telegraph readers happy.

These domestic vulnerabilities are continually exacerbated by other elite policy preferences. The Review notes the vulnerability of undersea cables and the UK’s growing dependence on them, but fails to discuss the merits of the policy of importing 10% of the country’s electricity supply (and on some days more like 20%). There is no particular reason why the UK needs to be as reliant on interconnectors as it has become, beyond the elite preference to reduce domestic emissions in the power sector. In this light, the Review’s rhetoric about an ever-more dangerous world rings hollow. Has no one told the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero? Interestingly, the authors note that they worked closely with the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Defense, but the Home Office, DESNZ, and the Foreign Office in particular are all notable by their absence.

To give the Reviewers their due, the document contains a wide-ranging number of very reasonable suggestions for improving the functioning of the MOD. Undoing the disastrous Levene Reforms and centralizing authority under the Chief of Defense Staff has considerable merit, with procurement likewise becoming increasingly controlled by the National Armaments Director. This should do much to sidestep the chronic problem of inter-service rivalry. The Review likewise acknowledges the importance of getting as much as possible from existing assets such as aircraft carriers through naval drone development. But all of this is in service of an Equipment Plan dominated by two giant megaprojects, AUKUS and GCAP, that both come with huge political and technological risks. Reactor development for AUKUS (and the Dreadnought class missile submarines) has already been red-flagged by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, while funding for GCAP is every bit as much at the mercy of future Italian and Japanese governments as it is the Treasury.

Meanwhile, the nuclear establishment eats up ever more of the budget: the Review itself says that £15 billion will be spent within this Parliament on the next generation of warheads for Trident. This is a truly stunning figure: as Gabriele Molinelli points out in his excellent review of the Review, this is approximately the sum that the U.S has dedicated to an equivalent capability, but in the American case spread over far many more warheads and years. Either something has gone spectacularly wrong with the British nuclear weapons development program and costs have secretly exploded, or far more is being bundled under his headline figure than the MOD wishes to acknowledge. Either way, the entire Defence Nuclear Establishment is forecast to devour at least 18% of the annual budget going forward. None of this says good things about the affordability of the envisaged future conventional force. All of these very obvious problems are, once again, completely ignored.

Instead of this dubious exercise, it would have been as well to spend some time doing some more fundamental thinking. Does unconditional and perpetual support for Ukraine really advance the national interest? Why does China need to be a “pressing challenge” rather than a partner in economic development? What is the UK actually getting out of the “special relationship”? What have we ever got out of it, since the end of the Cold War? Even before then, the U.S showed little interest in helping Britain defend the Falklands from aggression. What is a foreign policy that is both fiscally affordable and politically sustainable, given high peacetime deficits, very limited fiscal space, growing spending pressures from an aging population, low productivity, continued deindustrialization, the collapse of the two traditional parties in the polls and the rise of an anti-status-quo movement to the position of favourites to win the next election? Unfortunately, however, for a regime essentially on autopilot, such fundamental questions will usually be unasked and most certainly unanswered.