Episode Twenty: The Ghost of John Paul Vann

With Afghanistan firmly back in Taliban hands, there have been remarkably few Vietnam comparisons, perhaps a sign that the collective cultural memory of that war is very faded now. To some degree, this betrays a certain wisdom. The Viet Cong were better armed and far more disciplined than the Taliban. Afghanistan has no equivalent of the Battle of Ap Bac, where a numerically inferior and lightly armed VC force withstood and repulsed the South Vietnamese “Army of the Republic of Vietnam” (ARVN) and their American advisors in pitched battle, destroying five US-operated helicopter gunships and repelling attacks from armoured personnel carriers.

Vietnam, though, extensively demonstrated the difficulty of the “train and advise” model of Western imperialism, long before we had to relearn those bitter lessons in Iraq and Afghanistan. All the same problems of the backseat driving approach to counterinsurgency manifested themselves in Vietnam: no one speaks the local language or really understands the political incentive structure.

Even men of the calibre of John Paul Vann, one-time advisor to the ARVN and later, by an odd quirk of bureaucratic fate, the first civilian to ever lead US troops in combat, could not overcome the inherent impossibility of the mission they confronted. Vann, whose life and deeds are chronicled Neil Sheehan’s epic A Bright Shining Lie, was the rare sort of warrior who excelled in fighting not just the Viet Cong, but also his own army’s bureaucracy. His weapon in that war was the media. Vann leaked and briefed remorselessly in desperate and only partly-successful attempts to ensure McNamara and the Joint Chiefs in Washington could not ignore the reality on the ground.

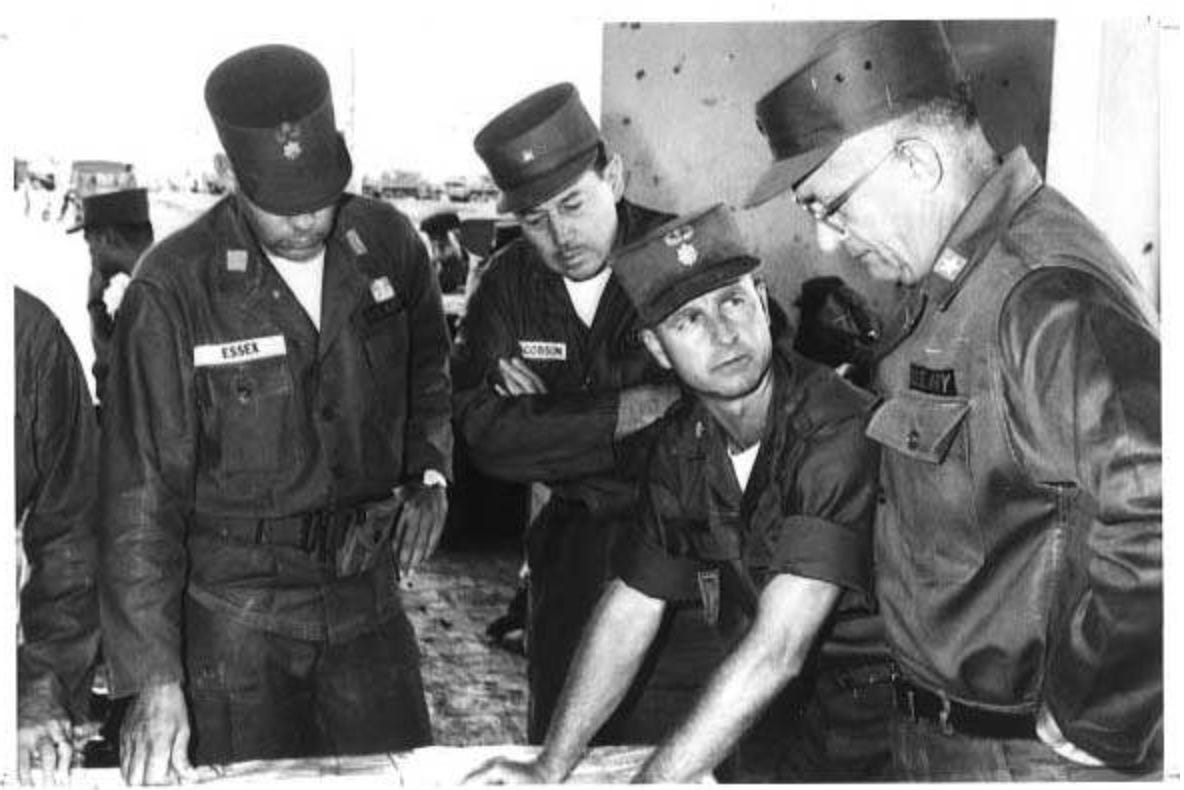

Vann, second from right, briefs fellow advisors.

A few quotes illustrate how grim that reality was, and how the failures of the ARVN bear an eerie resemblance to those of the hollow “Afghan National Army” the US built up at enormous expense forty years after.

With the exception of the airborne battalions and the Saigon marines who [General William] Westmoreland employed on his search-and-destroy operations, the regular ARVN avoided combat assiduously after 1965….the 18th ARVN Division at Xuan Loc claimed to have conducted 5,237 patrols and other small-unit operations over the five-day period. They reported making contact with the enemy thirteen times. “I can easily establish more enemy contacts on a daily basis myself”, Vann wrote.

….

Vann and his friends were sufficiently steeped in the realities of Vietnam to understand that the Saigonese [elites] were a socially depraved group with no capacity to reform or sustain themselves….[Ambassador Henry Cabot] Lodge, Dean Rusk, and [President] Lyndon Johnson convinced themselves that Nguyen Cao Ky, who had himself named prime minister by his fellow generals, really was a prime minister of sorts, and that Nguyen Van Thieu, who had connived his way into being appointed chief of state represented something besides himself and his title.

…

He pointed, sweeping his finger from one charred remembrance of a home to another. “Here is your American AID!” The farmer spat on the ground and walked away.

Between them, these extracts hopefully convey something of the flavour of Vietnam: an shell Army that cannot and will not fight, local political elites play-acting at governance while cheerfully looting as much cash as possible, and American firepower that is insufficient to truly cow the peasantry, but causes enough pointless destruction to drive young men into the arms of the insurgency.

As a great philosopher once said, “it’s like poetry, they rhyme, every stanza kind of rhymes with the last one”. This leaves the question, though, that John Paul Vann’s ghost would surely ask: why does the US keep falling into the same pattern? Why can it not learn from failure?

It may be the case that the undoubted excellence of the US military is a hidden handicap. It has been a long time since the US had to fight a war with a civilian army of modest quality. WW2 Generals like Omar Bradley knew full well that their troops were not up to the standards set up by Wehrmacht, and planned their battles accordingly, relying on overwhelming firepower to compensate. His successors, leading professional troops among the best in the world, have not learned the habits of compromise.

Killing does not come easy to many men. Under fire, the mind and body naturally freeze up (if you’ve never been paintballing, try it!). It takes not just extensive training but years of immersion in a rarefied military culture of excellence to overcome these powerful instincts. Suicidal bravery, of the sort needed to overcome an well-positioned enemy force, is always hard to come by. Blinded by its own high standards, codified and embedded over decades, it may be that the US simply did not realize what it was asking of Vietnamese and Afghans lacking any professional martial traditions.

By contrast, the small minority of Vietnamese troops who did come from an established professional military culture, the battle-hardened paratroop forces trained by the French, outperformed the regular army by a vast margin throughout the war. For all Vann’s scathing words about the ARVN’s showing at Ap Bac - “a miserable damn performance” - he did not regard the Vietnamese as a cowardly people, not least because of his appreciation of the achievements of the Viet Cong. The ordinary troops of the ARVN he viewed as men that could be molded into a competent force if they were given proper leadership. Yet this leadership was never provided, and, as in Afghanistan, the US was always reluctant to established truly mixed units, with the Vietnamese learning their battlefield craft alongside Americans, under American leadership.

Behind this all lurks the spectre of American anti-imperialism. The global hegemon is a nation that does not conceive of itself as an empire, and so will not impose direct political rule on the nations it conquers. This leaves American objectives ultimately dependent on the competence of local elites. Sometimes this works out, but when it fails, the US is left with no recourse. Once upon a time, it would have installed a proconsul, as in Japan, but ever since Truman’s relief of MacArthur, American presidents have proved reluctant to assign both political leadership and military command to one man. In Iraq, Paul Bremer never had any meaningful control over the US military, and his key political decisions - dissolving the Iraqi Army and mass de-Baathification - were made by others.

For now, the era of population-centric COIN is done, its practitioners discredited. This is bad news for the King’s College War Studies department, but probably good news for the armies of the West. Their brainpower and budgets can now be spent on catching up to Russia and China in key areas like artillery, long-range precision missiles, and ground-based air defence. But it would be foolish to assume they will never again be called upon to fulfil the kind of role at which they failed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Before we do this again, it would be good to resolve the inherent tension between claiming to fight for the betterment of the local people while simultaneously subjecting them to the depredations of men like Hamid Karzai and Nouri al-Maliki.

The lack of a well-prepared proconsular ruling class, though, would be a serious barrier to America moving away from a policy of propping up corrupt and factional local elites. While some farsighted donors seem to have funded an undergraduate & masters-level program at Yale to prepare the proconsuls of the future, Tanner Greer at Scholar’s Stage reports that the course has lately been hijacked, becoming a training ground for social activism in the US itself. Even if the lessons of Vietnam and Afghanistan are learned, the hegemon will likely remain essential narcissistic, trapped into an ever-tightening obsession with its own social concerns.