Episode Two: The Kids Are Alright

My favourite type of kid you find in classrooms is the Honest Trier. The Honest Trier is not very bright. At best they’re making “expected progress”, generously interpreted. But they put their heart and soul into their work. Usually the Honest Trier is a girl, but sometimes they’re boys. Their handwriting is good. They can learn and apply rules, just about, on a good day. Their parents will be baffled by their spelling and grammar homework, but the Honest Trier is secretly in their element.

Abstraction and inference, though, are entirely beyond them. Maths questions framed as word problems are their kryptonite. At the lower end of the Honest Trier spectrum, they can decode just fine, but never truly learned to read. At the higher end, they can read books rather less advanced than you would wish, and their own creative writing will be shocking unless you painstakingly scaffold it for them.

Honest Triers are the great joy of primary school teaching. At secondary, they rapidly figure out that education is, as a wise philosopher once said in a different context, “a totally corrupt, RIGGED system”. They come to secondary in Year 7, see themselves surrounded by disaffected, bored teenagers forever stuck in bottom sets, and quickly accept their fate. The gap will never close, as their primary school teachers never quite promised but often implied. It will only get bigger. They give up.

People who don’t work in education have usually forgotten quite how big those gaps are. Already by Year Three you have some kids two years ahead, others two years behind, still struggling with their number bonds to 20 - stuff they’re supposed to master in Year One.

In one Year Four class you find children like Faith. Her maths was merely Year Six standard, in a school with bad maths teaching and generally low standards. Her English was exceptional, with creative writing on a par with what you might expect from promising GCSE students. I used to read her stories for pleasure. I suppose I should have tried to offer some suggestions for improvement, but that would have seemed rather churlish. Given a few years of mild pushing, she could have aced her GCSEs at the age of eleven.

In the same class as Faith, you also find children like Jessie. Jessie didn’t have any kind of diagnosable learning difficulty or problems at home, but was already comfortably a good two years behind where she should be for most things, and four years or more behind Faith. Jessie, however, was precocious in one way. She had rightly figured out that this whole education business is a black farce and the returns to effort are negligible compared to the returns to brains. Honest Trying is for the birds.

For Jessie, school was about her social life. She was bubbly and vivacious, with a great sense of humour, and lots of friends. Learning was what got squeezed in occasionally between extended bouts of gossip at the back of class. I never really had the heart to tell her off. I hope she does well in life. I think she will.

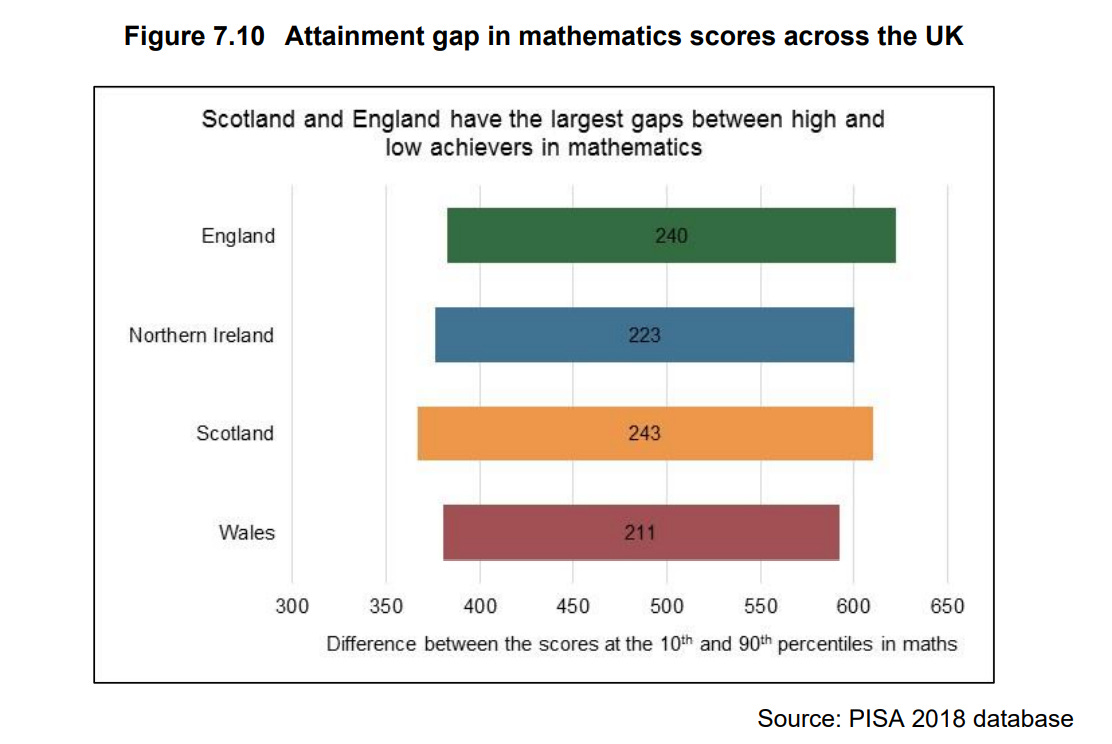

At secondary, Faith and Jessie diverge ever further, as the cognitive complexity of the curriculum increases. At fifteen, when a sample of children sit the PISA tests, the gap between 90th and 10th percentile students is around 250 points - eight whole years of schooling.

Schooling doesn’t really maximize inequality, of course, but nor does it really minimize it very much. It just brings into progressively harsher light the differences that were there already since birth. If you put Manchester City and Accrington Stanley against a set of common opponents, starting with an under-11 boys team and ending with Bayern Munich, over time what initially seemed like a barely perceptible performance difference is shown for what it really is.

Real life, thank God, isn’t just one painful, exhausting intelligence test after another. We don’t lock adults in edu-prison and treat them like circus monkeys, unable to leave until they can perform a sufficient number of tricks to the ringmaster’s satisfaction. People can use muscles or looks or some combination of the two to earn a good living. Anyone with a charming personality can thrive in any number of jobs. Virtue and joy are about more than just brains. The wise teacher learns to love both Faith and Jessie for who they are. You can’t change the facts, just your reaction to them. In the end, the kids will be alright, and if they aren’t, there’s nothing you could have done to change that.

School, however, can never just be a place where loving adults watch the kids grow up. It has been and always will be one of the primary arenas where society’s collective anxieties about the future are worked out. As we live in ever-growing fear of our own technological advancement and eventual replacement by machines, so we keep cranking up the pressure on Jessie and her teachers to behave more like machines. Put teaching in, get learning out. These fears might be nonsense. They probably are. But we’re so terrified now that we’ll even send the kids to school in the middle of a deadly plague, lest Jessie miss any opportunity to close that unclosable gap to Faith.

Naturally, no one asked the kids what mattered more to them: the lives of their grandparents or yet another round of trying to learn how to divide on a number line (if that sounds like nonsense to you, it is). Children are pretty honest, but for adults, some truths are better left unheard.